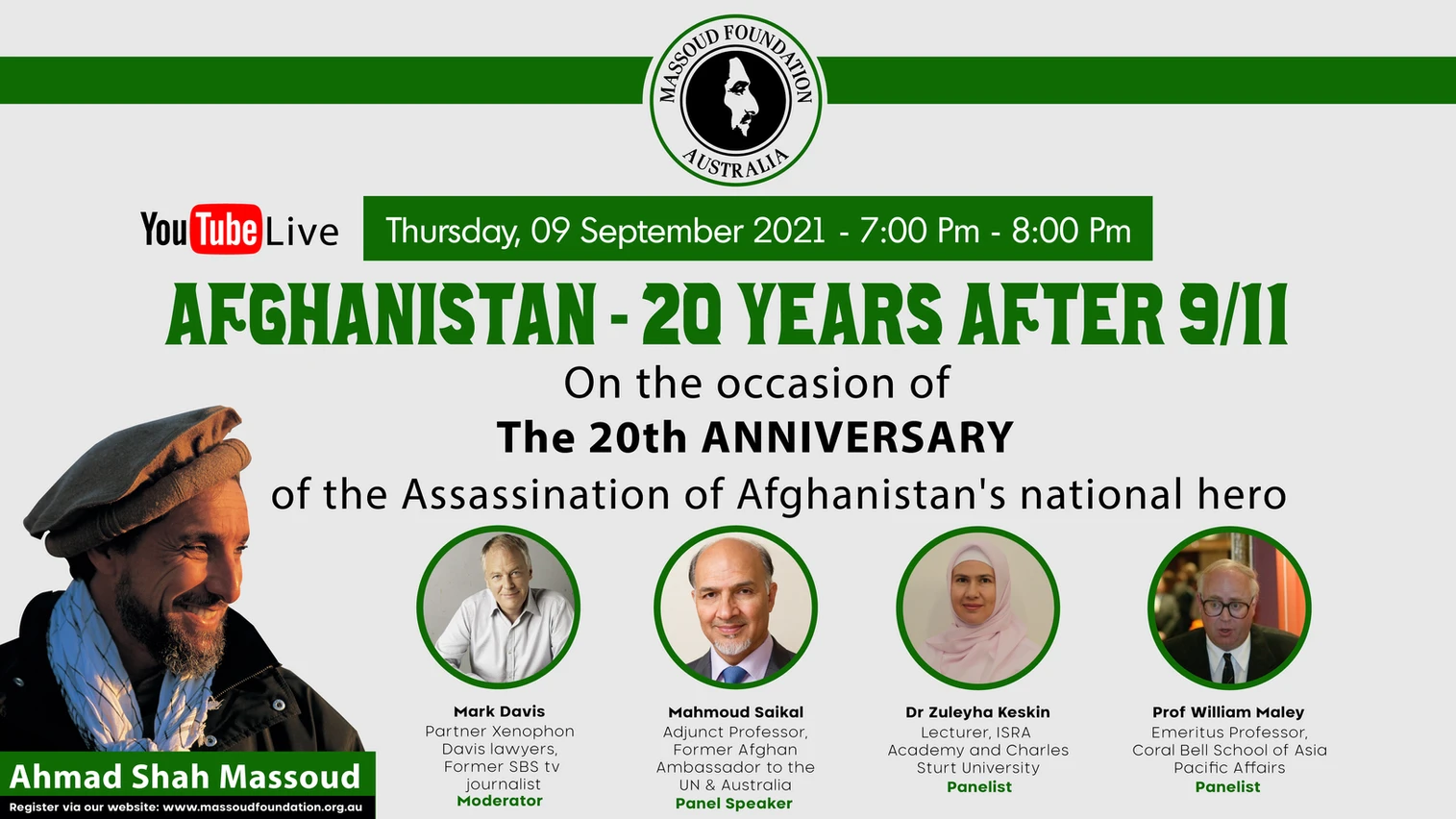

On The Occasion of The 20th Anniversary of The Assassination of Afghanistan’s National Hero, Ahmad Shah Massoud

Twenty years after his assassination, Ahmad Shah Massoud’s legacy remains potent and central in the politics of Afghanistan. His reputation in the West probably rests far more on his genius as a commander and guerrilla fighter than on how his ideas might contribute to Afghanistan’s future development and welfare. And it is true that he achieved astonishing military successes against the Red Army and that his campaigns were perhaps the most important single factor that led to the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Furthermore, some have argued that the Soviet failures in Afghanistan were a major contributory factor in the demise of the Soviet Union itself. Within Afghanistan, as well, Massoud’s rise to fame came with his military achievements. He is seen as the greatest symbol of national resistance – comparable to De Gaulle in France. After his assassination in 2001, Massoud was officially named as the ‘National Hero’ of Afghanistan, and September 9th, the anniversary of his murder – Martyr’s Day – is a national holiday.

Massoud’s legacy should not, however, be reduced to his military and strategic genius. He had a coherent set of political, ethical, and religious beliefs, and neither his character nor his career can be understood without taking these into account. If he is important for Afghanistan’s future as well as its past, this will be because his ideas and loyalties have value.

In fact, Massoud’s legacy is not uncontroversial within Afghanistan. Although he has indeed become a symbol of sacrifice, national independence, and resistance for many, to others, his legacy is contested, for he not only fought against a foreign enemy – the invading Soviet Red Army along with its client the regime in Kabul – but he later opposed the conglomerate of the Taliban and Al-Qaida other extremist groups (also known in Afghanistan as the Black Army).

Internally under, first, a centralising monarchy, then under Communist client regimes, and even after the fall of Communism, there has existed a tightly centralised state with different ethnic groups, where the temptation is for one ethnic group to use this centralising tradition to assert a claim to hegemony. So both external and internal forces combine to make Massoud’s vision of a free and independent country difficult to realise.

In other words, Massoud rejected both foreign domination and an internal ‘factional domination’ and his grounds for these rejections are to be found in his convictions about social justice and harmony which both stem from his understanding of Islam and the history of the region. Massoud always insisted that he was fighting for an independent and free Afghanistan, allowing its citizens to freely agree on the democratic arrangements under which they will govern themselves.

For Massoud, this idea was not at all as truistic as it might sound, for he related it firmly to Afghanistan’s history and its geopolitical position (one might even say, ‘predicament.’) Afghanistan lies at the intersection of West Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia. Externally, neighboring powers (the British Raj, Imperial and then Soviet Russia, Pakistan) have often sought to treat Afghanistan as a client or a buffer state. There was, therefore, the danger that the country’s sovereignty might exist in name only.

Thus an emphasis on context is as important as the man, and hence the title of this seminar. As mentioned, in the eyes of detractors and harsh critics Massoud never achieved a national leadership above the fray of ethnic communal politics. Massoud and his followers stand accused of human rights abuses during the 1992-1996 conflicts in Kabul.

In addition, that period is known for some as above all the era of ethno-regional conflict, while proponents of Massoud argue that they were fighting against several proxy forces of countries in the region, which had plans to install a friendly (or puppet) regime in Kabul and promote sectarian agendas in the country.

The Key Phases of Mssoud’s Career:

First, his early formative years as a young student in Kabul and his escape to Pakistan. This escape to Pakistan was primarily motivated by Massoud’s religious convictions, especially by his belief that Islam was under serious challenge from Communist power in Afghanistan. It is vital – especially for Westerners – to understand the place of religion in Massoud’s life, and not to downplay it.

At the time of his flight to Pakistan, it would be reasonable to describe him as an Islamist. It might be easier in the West to understand him as a liberal or progressive – and indeed he espoused democracy, pluralism, and the rights of women. But all of this was within an embracing religious faith.

He was devout – praying the prescribed prayers even in the heat of battle. His humanitarianism – as shown for instance in his treatment of captured Soviet soldiers – sprang also from religious convictions.

He was a Sufi and also a passionate lover of poetry – which he encouraged his soldiers to join him. In the past people in the West have understood and respected the idea of an Islamic warrior: in the Middle Ages Saladin was actually a hero in Europe despite being also seen as an opponent.

It would be a pity if the current experience of Islamist extremism were to obscure that very important aspect of Massoud’s life and character.

Secondly, his role in establishing and leading an effective guerrilla resistance movement against the invading Soviet forces for ten years (1979-1989), strategically cutting the landlines between the Soviet forces in Kabul and the HinduKush Salang Pass.

Thirdly, his role in overthrowing the Najibullah regime after the Soviet withdrawal and ensuring the independence of Afghanistan (1989-1996).

Finally, his establishment of the National Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan, which is also mistakenly labeled as the ‘Northern Alliance,’ in order to fight against the Taliban and Al-Qa’ida forces, groups whose chief support was from Pakistan. It is important to mention that after the takeover of Kabul by the Taliban; only three countries recognised the Taliban regime: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Time & Location

09 Sep, 7:00 pm – 8:00 pm AEST Online Webinar

Moderator:

Mark Davis, Partner Xenophon Davis lawyers, Former SBS tv journalist

Panel Speakers:

- Mahmoud Saikal, Adjunct Professor, Former Afghan Ambassador to the UN & Australia

- Prof William Maley, Emeritus Professor, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs

- Dr Zuleyha Keskin, Lecturer, ISRA Academy, and Charles Sturt University